Your great aunt Lizzie or great grandma Eliza could be your link to a $700,000 cash windfall thanks to a stranded inheritance in a Royal bank account in London.

Your great aunt Lizzie or great grandma Eliza could be your link to a $700,000 cash windfall thanks to a stranded inheritance in a Royal bank account in London.

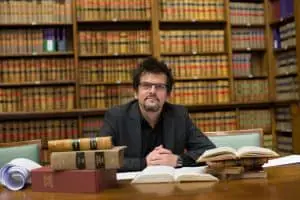

Expert “heir hunter” Daniel Curran knows well the line sounds like a scam email, but he is in Boston making the pitch because it’s his last hope.

Curran, founder of Finders International and star of the BBC reality series “Heir Hunters,” is short on leads in the three-year-old case to connect a London woman’s stranded inheritance with her next of kin.

Kathleen Hilda Ryan died in 2013 in south London with no children, no will and a $700,000 estate. Curran saw a notice about the estate and started digging through her family tree to find a next-of-kin, but in line after line, no living relatives could be found.

For Curran, Kathleen Ryan’s aunt Lizzie Ryan — who also went by Eliza and Elizabeth — is the last promising branch.

Born in February 1878 in the town of Mullingar in County Westmeath, Ireland, Lizzie Ryan emigrated to New York City in September 1906, to stay with a friend on West 56th Street. She later moved to Boston. That’s where the trail runs cold, Curran said. She’s in no public records and doesn’t appear in the U.S. census. But that doesn’t mean she didn’t put down roots in Boston.

“Someone might be reading this and remember a Lizzy Ryan from Mullingar in County Westmeath,” Curran told the Herald. “Someone might be out there sitting on a fortune. They don’t even know.”

The funds are kept in a royal bank account, where they earn interest for 12 years. After 30 years, the money becomes the property of the Queen, Curran said.

Often families have no idea there’s a deceased relative overseas, so the news of a windfall often opens up a family history they’d never discovered.

“We come to people with a story for money, and we come to them with a story of their family that they don’t know,” Curran said. “It’s not just about sums of money.”

In the world of international probate genealogists, most inheritances can be paired with a living relative, Curran said, but some can’t.

“It’s rare for a family to die out completely. When it does happen it’s frustrating,” Curran said.

This article has been first published in Boston Herald